Every crisis which affects capital markets gives us a chance to revisit and relearn certain ideas which might help us navigate in the future. The Covid-19 crisis in that regard is no different than all of the prior witnessed crises. Therefore, for today we decided to point out 3 lessons (re)learned so far during this crisis.

During a crisis it is valuable to see if there are any commonalities between stocks which underperformed and those which outperformed. Stocks which find their place in any of the mentioned categories usually tend to have some commonalities, which tend to be quite intuitive.

I) FLEXIBILITY MATTERS

The Covid-19 crisis confirmed the value of flexibility as more flexible companies (on a global level) witnessed significantly better share price performances than less flexible ones. To be specific, three types of flexibility seemed to be crucial for companies: investment flexibility, operating flexibility and financing flexibility.

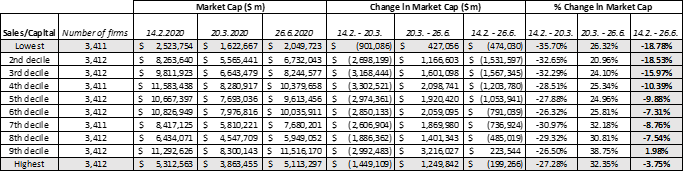

Investment flexibility in a sense measures how much a company needs to invest to get a given level of growth and how long a company needs to wait. The more a company needs to invest and the longer it needs to wait to achieve a certain level of growth, the less investment flexible it is (for ex. heavy infrastructure companies). A solid proxy for seeing how flexible a company is in this respect is calculating the sales to invested capital ratio. In the graph below you can observe the breakdown of global companies based on sales/capital ratio, which clearly shows a positive correlation between low investment flexibility and a poor share price performance (and vice versa).

Source: Aswath Damodaran, InterCapital Research

Operating flexibility measures how much your operating income is affected by a given change in revenues. Such flexibility was (and still is) particularly important in this crisis as the vast majority of companies observed a shock to their revenues to some extent. The main driver of the operating flexibility of a company is its cost structure, meaning that a revenue shock to a company with a higher share of fixed costs will lead to a much higher shock on the company’s EBITDA and operating profit than it would to a company with a higher share of variable expenses. A solid example of a sector with very low operating flexibility would be airlines, whose revenues were significantly hit during this crisis, but the share of operating expenses remained fixed.

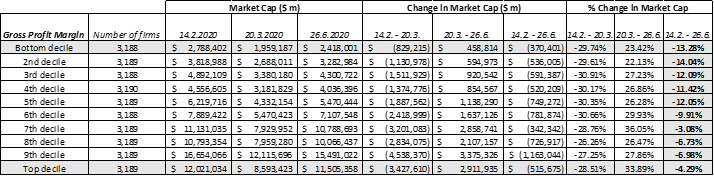

Measuring a company’s operating flexibility is quite challenging as it is difficult to estimate the share of fixed and variable operating expenses for certain companies. Damodaran for this used gross margin as a proxy as higher gross margin allows more room for a revenue shock. Although we can not conclude much from the graph below, it seems that globally companies with a higher gross margin have performed much better.

Source: Aswath Damodaran, InterCapital Research

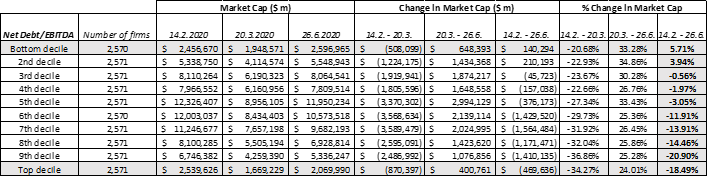

Financing flexibility measures how much net income changes for a given change in operating income. There are two main drivers of financing flexibility – how much debt a company decides to take and how much cash it decides to hold. Intuitively, companies with a lot of debt and not a lot of cash have very low financing flexibility. A solid representation of the financing flexibility is the net debt/EBITDA, which once again showed that companies with a higher net debt/EBITDA were hurt more that the one with a lower ratio.

Source: Aswath Damodaran, InterCapital Research

II) VALUE PERFORMED WORSE THAN GROWTH

This crisis also brought yet another debate on value vs growth investing and resulted in some interesting points. If we were to look at the US market and define value as a low P/E and P/B and growth as high P/E and P/B, one can notice that for the past 6 decades (by decade) value stocks have almost always outperformed growth stocks with the exception of 1990s (dot com boom). However, in 2010s we observed a reversal in the US, where growth outperformed value stocks (with an emphasis on FAANG stocks).

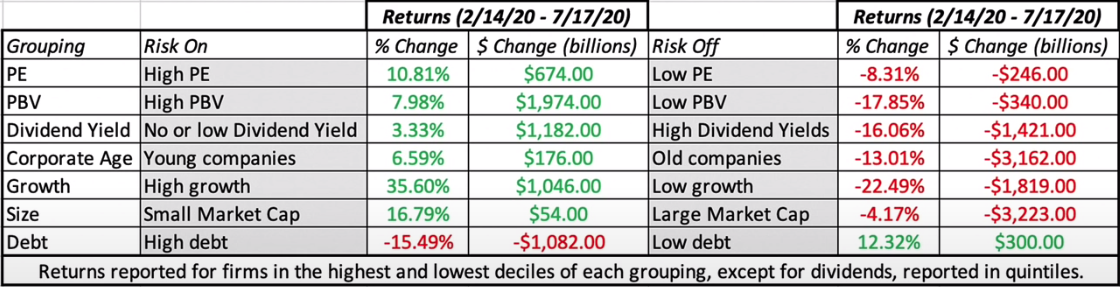

If we were to look at how these categories performed during this crisis, we reach an interesting conclusion. As visible from the table, what is considered as traditionally less risky (low P/E, low P/B, high dividend yield, low growth) has significantly underperformed since the outbreak of the pandemic. In that sense, this crisis is not like the previous ones. Note that the table represents the percentage change in collective market cap of top decile in its respective grouping.

Source: Aswath Damodaran, InterCapital Research

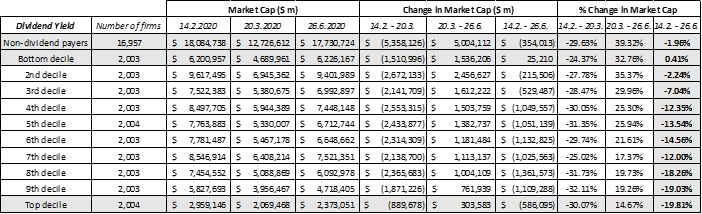

III) HIGH CASH RETURNING COMPANIES PERFORMED WORSE

A company’s dividend and buyback policy to a certain extent reflects the confidence to generate projected earnings and cash flows. Therefore, if companies lack or reduced their confidence of generating their projected earnings, they might revisit their dividend policy, reduce the dividend payment or stop buybacks. The Covid-19 outbreak has definitely had a negative effect on most companies projected earnings, which in turn led a halt in buybacks and dividend payments for many companies in 2020. As visible from the table, the high dividend yield companies performed worse than low dividend yield or non-dividend paying companies. If we were to include buybacks in the equation, we observed the same trend. However, the companies that only buyback stocks performed better than the ones only paying out dividends. This does not surprise us given that dividend payments are “sticky” while it is easier to stop buybacks without the share price being significantly punished by the investors.

Source: Aswath Damodaran, InterCapital Research