Starting from today, we’ll start to get a feeling of how much central banks are willing to deliver on their promises to reactivate accommodative monetary measures. The ECB will probably just sketch out a plan of further action, while the FOMC takes the driver’s seat next week.

Inflation expectations in the developed markets have been steadily decreasing since the middle of last year, mostly thanks to slower GDP growth prospects brought about by trade wars, Brexit, and economic expansion entering late cycle. It’s curious to note that for instance EUR 5Y5Y inflation swap dropped all the way down from 1.75% (June 2018) to the current value of 1.29% (FWISEU55 Index on Bloomberg, available here as well). The slide was accompanied by a cyclical weakness in high frequency data, such as PMIs, manufacturing orders, etc. Here’s one interesting indicator of how the perception of economic weakness has been developing: in January the IMF expected German GDP to expand in 2019 by as much as +1.3% YoY; in April this forecast was already cut down to +0.8% YoY; the latest, July forecast puts the figure at merely +0.7% YoY. With the current setup of macroeconomic figures, it wouldn’t surprise us to discover that the German GDP had decreased on a YoY basis in the second quarter of 2019 (GDP data would be published on August 14th).

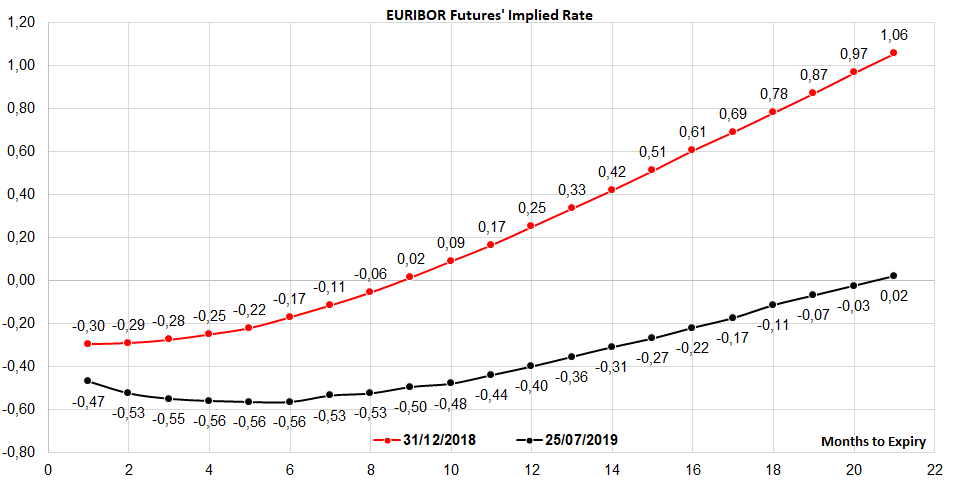

Here’s the funny part: although the growth slows down, the German DAX is up YTD by as much as +18.6%, while Eurostoxx increased by +17.71% since the new year kicked off. The underlying valuations are propelled by expectations of further accommodative measures in the developed countries that might be just around the corner. This is the reason why the financial markets will be listening closely to today’s monetary policy meeting – the interest rate decisions would be published at 13.45 CET, while the statement accompanied by Q&A session would be delivered at 14.30 CET. The chart submitted below (“EURIBOR Futures’ Implied Rate“) suggests markets are still unsure of which muscles the central bank plans to use, but it’s quite possible that a mix of interest rate cuts, asset purchase, and tiering might be introduced to sustain economic expansion and possibly revive inflation expectations higher. The recent central bank speak has been inclined to reviewing the inflation goal, and to understand it here’s a bit of a history lesson.

The EU Treaty only requires the Frankfurt-based institution to “maintain price stability”, without closely defining what that actually means. Until 2003 this objective was interpreted by ECB as keeping inflation below 2.0% figure, and then in 2003 the objective was changed to keeping it “below but close to 2.0%”. The change was decided behind closed doors and contributed to the perception of the ECB as an arcane, autistic institution. Sixteen years later another change in ECB policy might be around the corner, and this time the Chair of the GC pushes for “symmetrical” approach, meaning that the economists in charge could let the inflation move above 2.0% in the short run in order to ensure the stability of price growth.

During the secular period of sluggish inflation numerous ex-central bank officials have suggested different solutions for reviving inflation. For instance, ex-IMF Chief Economist Olivier Blanchard advocated moving the goal from +2.0% to +4.0%, but the ECB has spent the last 20 years building up credibility for being consistent to it’s inflation goal; merely changing the figures might cripple this credibility since it sends out a message that goals would be changed if their start to appear unattainable.

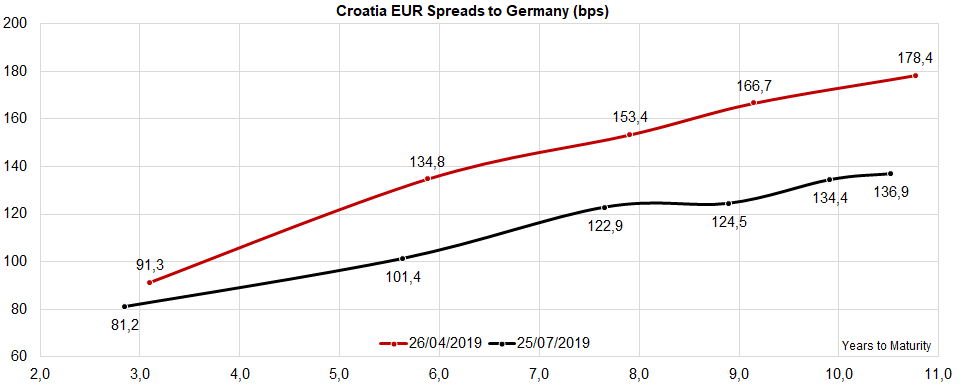

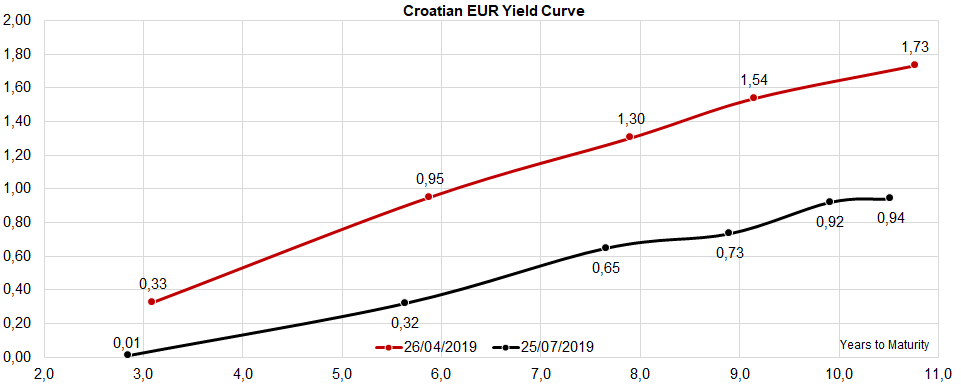

Our baseline scenario for today’s ECB Monetary Policy meeting is that nothing changes in terms of interest rates, but ECB starts sketching out a plan for the introduction of monetary stimulus, expected to be enacted in September. The effects are visible across the board: the euro dropped by about 150 pips in one week’s time, Bund trades at -0.39% YTM, while EURIBOR futures expect a 10bps rate cut in the near future. The effects are spilling over into EMs such as Croatia, although the contraction of the spread also has roots in a shift in credit rating, as well as expectations of entering ERM II as soon as next year. A couple of years will certainly go by before the ECB can purchase Croatian Eurobonds, but the portfolio effects are already here, warranting further contraction of CROATI risk premiums.