Iran has once again threatened to close the Strait of Hormuz, but oil prices are still not panicking. Prices have rallied around 10% since Israel began its attack on Iran more than a week ago and are now close to a five-month high, but this is all very subdued considering the implications this conflict can have.

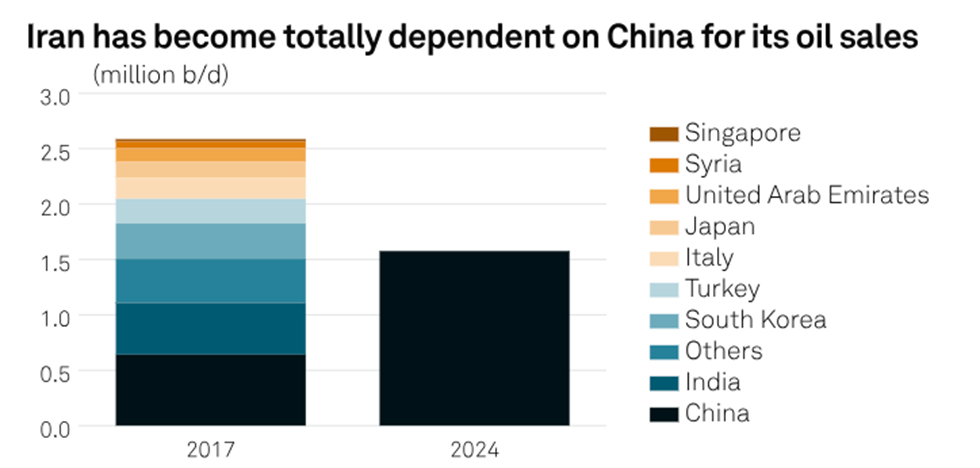

Iran, the third-biggest OPEC producer (despite U.S. sanctions), pumps around 3.3 million barrels a day of crude oil and exports roughly 1.7 million barrels a day. The loss of this export supply would wipe out the surplus that was expected in the fourth quarter of this year. Nearly all of Iran’s oil is shipped to China via the so-called “shadow fleet” — a group of nonregistered tankers used to smuggle oil into Asian markets. This dependency on Chinese buyers, especially since the U.S. reimposed sanctions in 2018, makes it unlikely that Iran would shoot itself in the foot and close its only real export route.

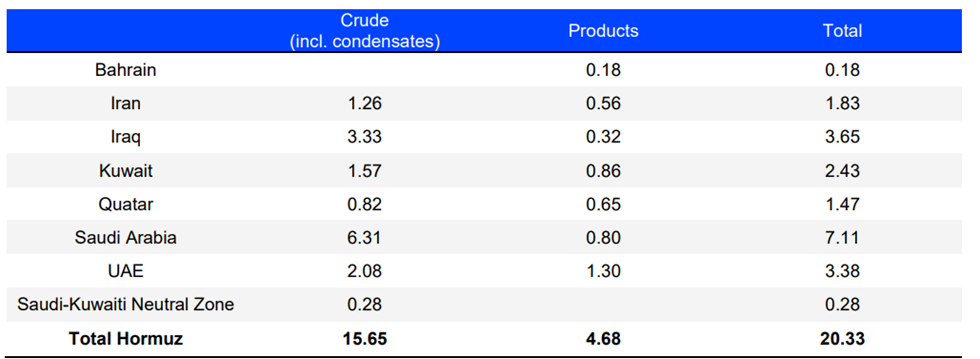

The Strait of Hormuz is a narrow waterway connecting the Persian Gulf to the Gulf of Oman and the Arabian Sea. At its narrowest point, the strait is about 21 miles wide, with two shipping lanes two miles wide in each direction. Around 20% of the world’s daily oil consumption — roughly 18 million barrels — passes through the Strait, with 70% of it bound for Asia. All LNG exports from Qatar and the UAE also transit through the strait, accounting for 20% of global LNG trade. There are no real alternative routes for these volumes. While 6.5 million barrels per day of crude oil could be rerouted via Saudi Arabia’s Red Sea pipeline and the UAE’s pipeline to Fujairah, these alternatives are insufficient to fully offset a serious disruption.

Exports through the Strait of Hormuz (mb/d)

Source: IEA

Although OPEC sits on 5 million barrels per day of spare production capacity, most of it is concentrated in Saudi Arabia and other Gulf countries that also depend on the Strait. Saudi Arabia can partially bypass the Strait of Hormuz using its East-West crude oil pipeline, but this alone cannot neutralize the impact of a closure.

Iranian officials began to taunt the Strait closure threat after possible U.S. involvement in Israeli strikes heightened. The U.S. — which had initially claimed it would take up to two weeks to make a decision — bombed Iran’s nuclear sites over the weekend, just days after signaling a slower deliberation process.

The situation escalated after Iran was found in breach of its nuclear commitments. The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) reported that Iran removed its surveillance and monitoring equipment in June 2022 and formally declared Iran in breach of its non-proliferation obligations in June 2025. Israel responded with strikes on nuclear facilities in Natanz and on Iran’s South Pars gas field.

The U.S. had been in talks with Iran about a new nuclear deal, one that would halt uranium enrichment in exchange for sanction relief, but negotiations failed. After Israel’s strike dealt significant damage to Iran’s nuclear program, some speculated Iran might return to the table. However, Israel was going to continue striking regardless and lacked the advanced bunker-buster weapons required to destroy fortified enrichment sites. Only the U.S. has that capability, which is likely why it joined the assault.

“If the United States officially and operationally enters the war in support of the Zionists (Israel), it is the legitimate right of Iran to pressure the U.S. and Western countries by disrupting their oil trade’s ease of transit,” warned Iranian lawmaker Ali Yazdikhah. “Closing the Strait of Hormuz is one of the potential options,” echoed Behnam Saeedi, a member of Iran’s National Security Committee presidium.

The threat is not without precedent. During the Iran-Iraq War in the 1980s, Iran mined the Strait of Hormuz and targeted oil tankers with missiles, including Chinese-made Silkworms. According to a 2012 U.S. Congressional Research Service (CRS) report, Iran could obstruct the strait gradually, starting with warnings, progressing to attacks or mining, and even potentially detaining ships. But such actions would likely provoke a massive American military response. Admiral Donegan noted, “They can do enormous damage to others… but they may not survive the blowback.”

Despite the rhetoric, Tehran has so far refrained from closing the strait because all regional states, and many global players, benefit from its free flow. Yazdikhah admitted that “mining also hurts Iran; they would lose income from the oil they sell to China.”

Iran oil exports (mb/d)

Source: S&P Global Commodities at Sea

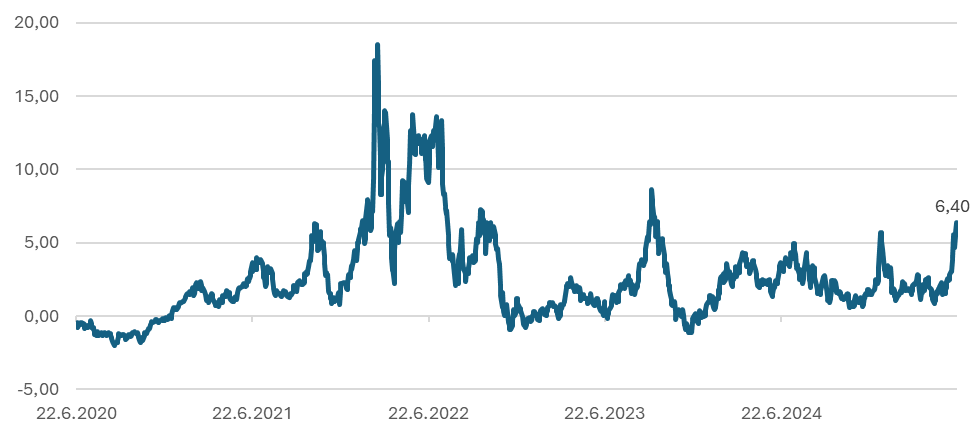

The futures curve is showing signs of concern about a supply shortage — the 1st vs 6th contract spread has moved beyond 2 standard deviations from its mean. But markets are still far from the stress levels seen during the Houthi attacks or the start of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. It seems traders believe history will repeat itself and that threats will be short-lived without significant long-term disruptions.

WTI calendar inversion

Source: Bloomberg, InterCapital

There are three plausible scenarios in which Iranian oil supply could be impacted:

- A more substantial effort by the U.S. Treasury or G7 to constrain exports, cutting Iranian oil sales by 50% or more;

- Direct attacks on oil infrastructure disrupting 1.5 million barrels per day for a couple of months;

- A deliberate Iranian closure of the Strait of Hormuz.

Yet, many believe the latter is unlikely. China, the primary buyer of Iranian oil, has been stockpiling crude in recent months. Chinese refiners often respond to price spikes by drawing on reserves and trimming imports. With this buffer, China may not panic even if flows are briefly disrupted.

Political betting markets echo this caution. On Polymarket, the probability of a Strait of Hormuz closure has fallen from 52% over the weekend to about 32% today. Meanwhile, WTI crude is only up 2% since Friday, implying that markets remain unconvinced these weekend strikes and rising threats will lead to a lasting global fallout.

The sheer volume of oil transiting the Strait of Hormuz — and the limited ability to reroute it — means any serious disruption could cause prices to spike toward $100 per barrel and result in physical shortages. But for now, both markets and policymakers are betting that the Strait remains open—unless Iran has absolutely nothing left to lose.