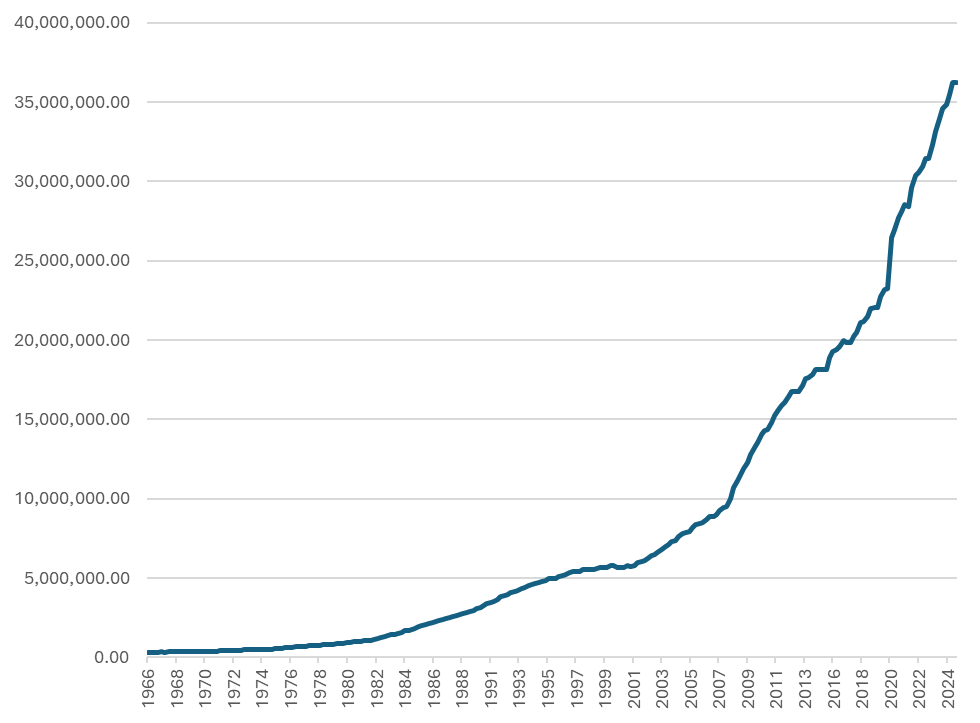

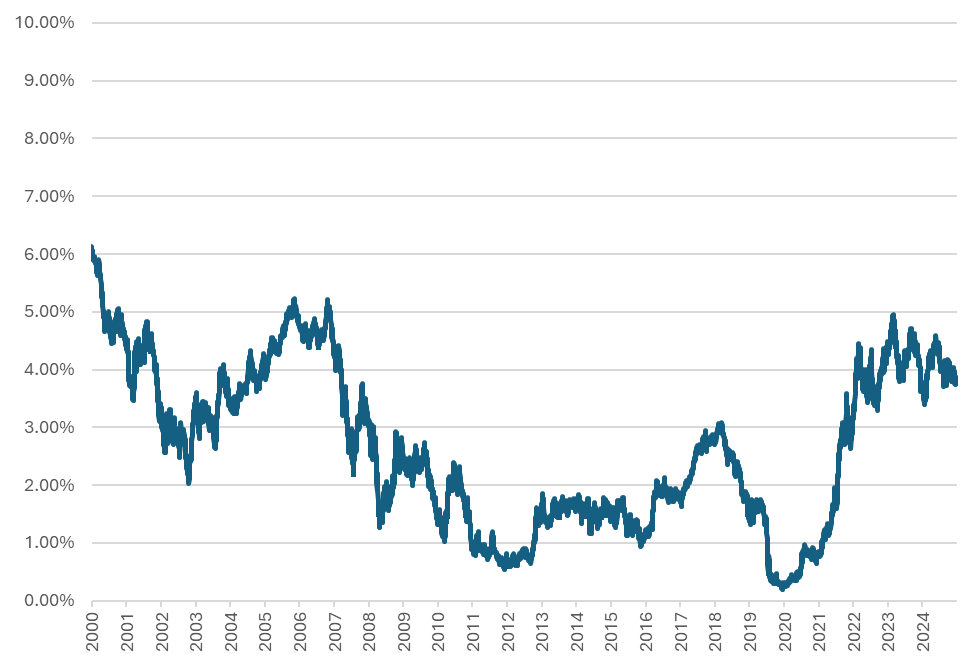

Since Trump’s arrival at the White House in January, he has strongly been advocating for lower rates, even going on to publicly attack the current FED chair, Jerome Powell, calling him a wide barrage of names. Trump’s thinking is simple: the US government debt has been rising to levels never seen before, and the rate they are issuing it is being issued is the highest it has been in more than 15 years.

US Federal Debt (USDm, 1966 – YE 2024)

Source: FRED, InterCapital

US generic Government 5-year yield index (2000 – 2024 YE, %)

Source: Bloomberg, InterCapital

He believes that by lowering the federal funds rate, he will be paying equally less on longer issued tenors as well. To set aside the economic logic behind this, and if the lowering of the federal funds rate would have any, if not the reverse effect on long-end yields, let’s take a look at the Federal Reserve, its independence, and if Trump can influence rate cuts.

A fragile independence

The Federal Reserve has historically enjoyed a degree of independence that is critical to its functioning. The idea is straightforward: monetary policy should not be directly controlled by elected officials who might be tempted to juice the economy before elections or soften the pain of fiscal mismanagement. Independence allows the Fed to set interest rates based on economic conditions, not political wishes.

But independence is never absolute. Presidents have often pressured the Fed, from Johnson to Nixon to Reagan. The difference with Trump is the public mocking tactic he has employed. Rather than quietly lobbying or exerting pressure behind closed doors, he makes public declarations, openly insulting the current FED chair, and surrounds himself with loyalists who share his view that interest rates should be cut aggressively.

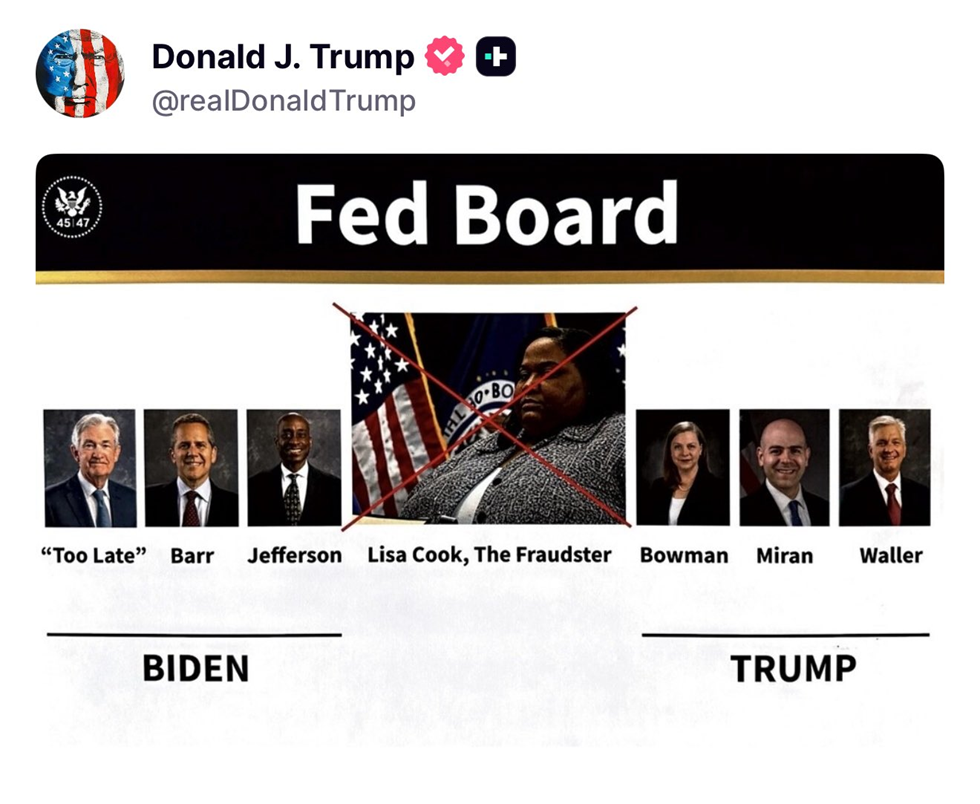

Trump’s allies inside the Fed

This brings us to the current composition of the Federal Reserve’s leadership. While Powell remains chair, Trump has been steadily trying to grow his influence inside. His most prominent ally on the Board of Governors is Chris Waller, a Trump appointee who has generally been more dovish than Powell. Another Trump dove inside the FED is Michelle Bowman, vice chair for supervision, who was appointed to the FED by Trump during his first term. Beyond the two, Trump has worked to place allies into vacant seats or into unexpired terms. He appointed Stephen Miran, chair of the Council of Economic Advisors, to fill an unexpired term left by Adriana Kugler. Miran likely will serve in the position only through January 2026, leaving a spot for the next FED Chair that Trump decides to pick. The Federal Reserve System is led by a seven-member Board of Governors, with the Board of Governors being part of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). Trump currently has Bowman, Miran, and Waller on his side. His most recent target is Lisa Cook, whom he accused of committing real estate fraud, which might get her kicked off the board. This will open up the possibility for Trump to appoint another ally inside the FED Board and regain the majority there.

Donald J. Trump’s post on Trump Social targeting Lisa Cook

Source: @realDonaldTrump

The FOMC, however, is a 12-person committee responsible for setting the nation’s monetary policy. Besides the seven members of the Board of Governors, it includes the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, and four other Reserve Bank presidents who serve one-year rotating terms. So, to regain controlling power in the FOMC, Trump would need 7 people. But one might imagine what else Trump’s team can find on the other members and use it to forcefully get them kicked out of their place and plant someone of their liking.

The Powell question

Powell’s current term as chair ends in 2026, but his governorship technically lasts until 2028. The open question is whether Powell will remain on the Board once his chairmanship concludes. Historically, some former chairs have stayed on, but often they step down, both out of respect for the institution and to avoid being overshadowed by their successor.

If Trump manages to place a loyalist in the chair seat, the dynamic between Powell and his successor could be tense. Powell might choose to leave early rather than serve under a Trump-appointed chair.

What this means for the Fed

Even if Trump doesn’t gain a full majority inside the FOMC, once Trump’s ally becomes Fed chair, the dynamic of the institution changes instantly. The chair sets the agenda at meetings, frames the discussion, and holds the press conferences that markets hang on. Even if other members disagree, most fall in line to preserve consensus and avoid open conflict. Staff research and analysis will start reflecting the chair’s priorities, reinforcing the case for easier policy. And with markets responding to the chair’s signals by pricing in cuts, pressure builds for the rest of the committee to follow through. In short, one loyalist in the chair seat is often enough to tilt the entire Fed toward Trump’s preferred path.

But, the danger here is not just about Trump lowering rates. Markets can adapt to lower or higher rates. Investors price in monetary policy shifts all the time. The deeper concern is institutional credibility. If Fed governors start to be removed, investigated, or sidelined for political reasons, the independence of the central bank is effectively gone. Future presidents, Democrat or Republican, would be tempted to do the same. Monetary policy would become just another partisan battleground.

This erosion of independence would likely backfire on markets as well. If traders perceive that the Fed is cutting rates not because of inflation trends or growth outlooks but because the White House demands it, confidence in US assets could decline again. That would ironically push long-term yields higher, not lower, undermining Trump’s stated goal of reducing borrowing costs.

Conclusion

Trump’s assault on the Federal Reserve is more than just harsh words aimed at Powell. It is a calculated effort to install loyalists and reshape the Fed into a more politically compliant institution. The Cook investigation, the planting of Miran, and the looming question of Powell’s future all point to a broader strategy: weaken the Fed’s independence and force policy shifts that align with Trump’s fiscal and political objectives.

Whether this succeeds depends on institutional resilience, on whether governors push back, on how courts view attempts to fire members, and on how financial markets react. But one thing is certain: the era of quiet, technocratic central banking is over. With Trump in the White House, the Fed is once again at the center of political warfare, and its independence has never looked more fragile.