One of the indicators of a strong and prolonged bull market is the appearance of leveraged ETFs in the media, in research reports, and even in academic papers. However, no matter how attractive this highly volatile instrument may seem after a long period of rising prices, it’s essential to understand it thoroughly to avoid ending up on the wrong side of returns.

Let’s start with the basics. A leveraged ETF is an investment product designed to provide investors (before costs) with exposure to a multiple of the daily price change of an underlying asset, usually an equity index. The key elements in this definition, which we’ll explain here, are that it is an ETF—with all the benefits and risks that come with such a product—and that it targets a magnified daily price change of the underlying index.

An ETF is an exchange-traded investment fund. It typically, but not necessarily, tracks a specific equity index, and by purchasing an ETF, an investor gains diversified exposure (and in the case of a leveraged ETF, amplified exposure) to index price movements without having to buy individual securities. ETFs are generally associated with low management fees, high transparency, and tax efficiency. On the other hand, beyond market risk, there are risks mostly tied to the ETF issuer and/or their counterparties.

Now that we’ve established that this is, at its core, an investment product familiar to the public, let’s focus on what makes leveraged ETFs unique. Primarily, we need to explain what it means to target multiple exposure to daily index changes and what the implications are for investors over short and long horizons and across different market regimes.

Leveraged ETFs achieve this amplified daily return through a Total Return Swap, a financial contract between two parties in which cash flows are exchanged based on the performance of a specific index. In short, it works like this: Party A (the ETF) pays Party B (the swap provider, usually an investment bank) an interest rate (e.g., SOFR + spread) and possibly a fee, in exchange for exposure to a multiple of the index return. If the return is positive, the bank pays the ETF the leveraged return; if negative, the ETF pays the bank. This structure allows the ETF to gain exposure without physically buying all the index constituents multiple times over. While these contracts are typically made with the largest and most reputable global banks, counterparty risk is still present. Additionally, paying interest and swap fees increases costs and replication error. Combined with generally smaller assets under management compared to 1:1 ETFs, this results in higher expense ratios—often more than the leverage multiplier itself. For example:

- NASDAQ ETF (QQQ): 0.20% expense ratio

- 3x NASDAQ ETF (TQQQ): around 0.95% expense ratio

Another critical risk is the potential for a sharp drop in the underlying index. When multiplied by the leverage factor, this can wipe out the entire position (e.g., -34% × 3 = -102%, or the entirety of the position).

We’ve defined a leveraged ETF as an ETF that offers exposure to a multiple of the daily index return and explained how it achieves that. Now let’s look at the consequences of such exposure for investors and when it generally makes sense to invest in these products—and when it doesn’t.

It’s important to understand that the fund resets its leverage daily, so performance over longer periods will almost always differ from the simple multiple of the index return—except by pure coincidence. The basic thesis is that this difference generally does not work in favor of the investor, though there are exceptions. Trending markets with low realized volatility are ideal for leveraged ETFs, which tend to perform particularly well in such environments, while in high-volatility regimes, a phenomenon known as volatility drag reduces returns. The main reason for both outcomes is the daily reset and the compounding effect of calculating leveraged returns on a higher or lower base each day. Let’s illustrate with a simple, intentionally exaggerated example:

Day 1: +10% → Index = 110; 3x Leveraged ETF = 130

Day 2: -10% → Index = 99; 3x Leveraged ETF = 91

Instead of a -3% drop (as 3 × -1%), the leveraged ETF fell by -9%.

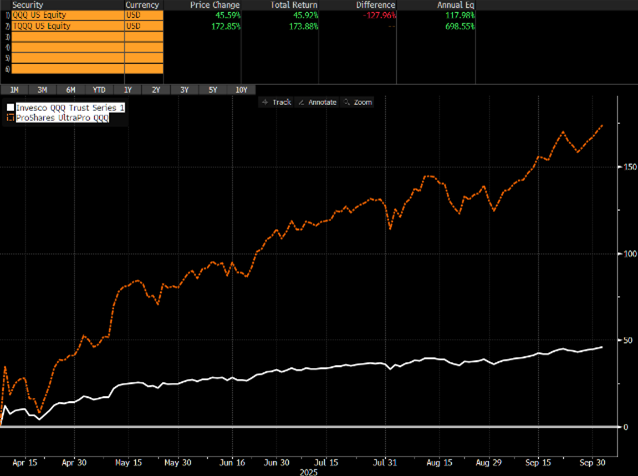

Volatility drag, therefore, can destroy significant value in volatile, range-bound markets, and the effect becomes more pronounced with higher leverage and longer holding periods. On the other hand, in a stable, upward-trending market with low volatility, a leveraged ETF can outperform the expected multiple due to compounding on a growing base. A real-world example of these dynamics can be clearly illustrated on a chart from this year—a year we know has been quite volatile—compared to the steady price increase after the April lows. For this, we’ll use the NASDAQ ETF QQQ and the 3x NASDAQ ETF TQQQ.

Comparison of cumulative returns: 3x Leveraged ETF (TQQQ) vs. Replicating ETF (QQQ) on NASDAQ

Source: Bloomberg, InterCapital

Leveraged ETFs can be a powerful tool for investors who understand how they work and use them in the right context. However, due to higher costs and the effect of volatility drag, holding these instruments long-term is rarely optimal. Without proper knowledge and strategy, a product designed to amplify gains can just as quickly multiply losses.