For the past four weeks fixed income trading reminded us of old sitcom reruns: although something happens in each episode, at the end everything returns back to normal and nothing has changed. If you miss an episode, you can easily tune in into the next one without losing the big picture. German Bund has been moving within -0.40%/-0.60% target band entire summer, so if you just came back from summer vacation and turned on your terminal, you probably see it exactly where it was before you left. Nevertheless, there might be some quiet forces below the surface that will affect global rates and that have just recently started to emerge. Which forces are we talking about? Find out in this brief article.

First of all – virtual Jackson Hole. Make no mistake, this was a major event this summer and the muted reaction came about simply because the virtual conference was all “talking the talk” and investors still need to see “walking the walk” part. The dovish shift announced by Jerome Powell had at least two important implications for the global rates market. First of all, in an era of strong global disinflationary forces and ample labor market slack, pre-emptive FED fund rate hikes are a thing of the past. Basically, in times like these even the FED is not worried about inflation getting out of hand. At the same time, this effectively means that FED fund hikes put in force through Yellen’s term as FED’s chairwoman were the wrong thing to do, at least in hindsight. If you think that if Yellen hadn’t raised interest rates, then Powell couldn’t have helped the corona-affected economy by reducing them, don’t forget that we’re not talking about FED that existed twenty years ago and had only one or two instruments in the toolbox. Instead, today’s Federal Reserve has a plethora of instruments that target specific sectors of the economy and in 2020 we would be able to examine how successful each one of them was.

Second important takeaway from Jackson Hole is definitely the abolishment of the hard 2.0% inflation target. Instead, the FED would tolerate inflation overshoots in order to make up for the decade of week inflation. Speaking about the second takeaway, one must ask himself – well, why haven’t the long term rates drop like stone? As we mentioned before, the reason lies in the fact that investors still need to see “walking the walk” part. In other words real measures and actions. That’s why all eyes are now on September 16th FOMC meeting and the main question hovering above our heads is: could it be that more stimulus might be under way? Well, the risk markets are expecting something – additional QE, extended forward guidance, or a combination of two. If this doesn’t happen, risk markets might be facing a mild, contained correction. That means lower equities, higher VIX and wider risk premiums, however this is only in case the FED disappoints. And even if it does, it’s quite likely it would deliver something to back up new policy framework on the next FOMC meeting.

Jonathan Golub, chief rates strategist for Credit Suisse, summarized this policy framework move in two brief sentences: “We’ve had 30 years of Japan doing very, very aggressive policy, and you didn’t get either inflation or growth there. Why do we believe we are going to be different?”

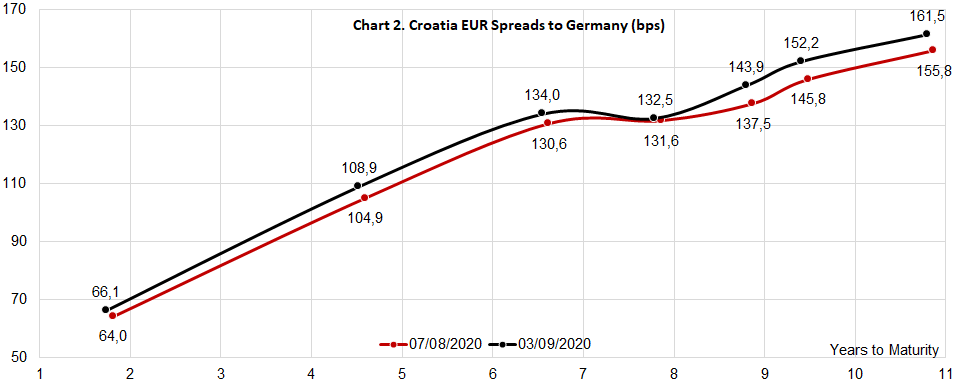

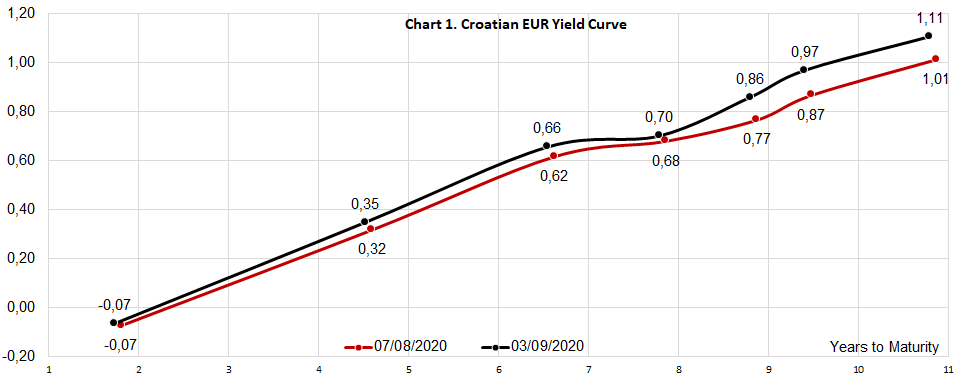

Turning our attention to Croatian eurobonds, Chart 1. suggests that yields moved up by as much as 10bps on the longest one (CROATI 1.5 06/17/2031), 5.7bps coming from wider risk premium (Chart 2., 5.7bps = 161.5bps – 155.8bps). Most of the move came in last two or three days when German Bund rallied and Croatian bonds didn’t really follow suit so the gap opened up. We stick to the belief that the spread might start tightening any time soon since we do see some switching from front and belly of the eurobond curve to the far end. Also, in an environment like this, ultra-long local bonds are a good place to be if you can hold these even with illiquidity risks hovering around your head. Additional benefit lies in the fact that with euro area accession, servicing of Croatian public debt will continue to decrease as old bonds are rolled over at more favorable terms, keeping the interest rate component of the deficit on a downward path.