With all that has happened so far in 2022, we decided to bring you an analysis of the current situation of the oil and its derivates prices, as well as a general overview of the fuel prices in the EU, as well as answer the question: Why are the fuel prices so high and what can be done to mitigate this as much as possible?

With 2021 bringing strong vaccination rates and a relaxation of COVID-19-related measures, personal consumption began to pick up as more and more countries opened their doors. This trend continued in 2022, and with that surge in available cash, so did inflation. However, even though this was considered only „transitory“ at the time, the Russian invasion of Ukraine has made all of the projections and forecasts for the year null.

This has especially proven to be the case for the commodity markets, particularly in regards to oil, gas, wheat, and precious metals, the commodities that are exported from Russia, (but also Ukraine, when it comes to wheat and metals). The whole situation has sent the prices of commodities spiraling, and in this blog, we’ll focus exclusively on oil prices and their derivates, to see how much influence will the current situation have on supply and demand, as well as the fuel prices consumers pay.

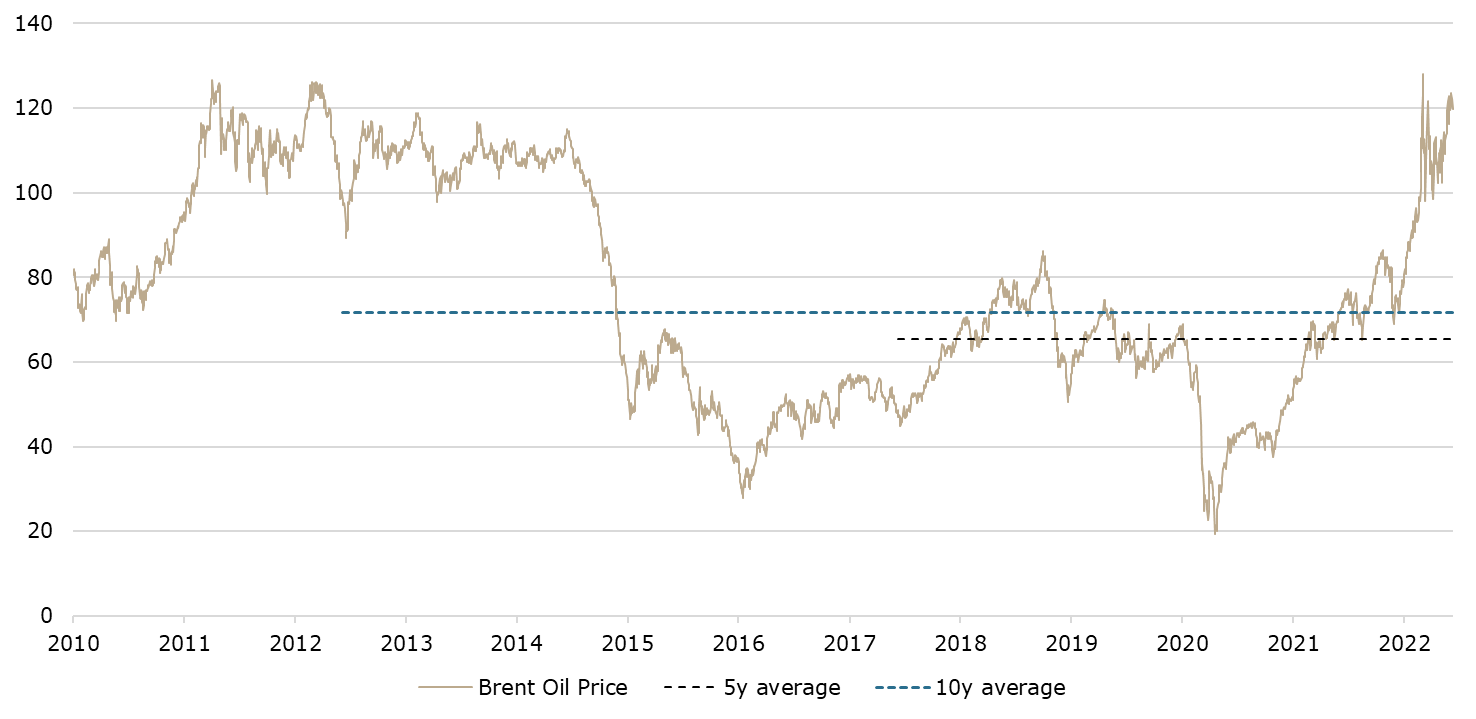

After the start of the invasion, prices of oil skyrocketed to multi-year highs, reaching a maximum of 127.98 USD/bbl (Brent price). As a point of comparison, oil prices hovered at 71.72 USD/bbl on a 10-year average, while on a 5-year average, they amounted to 65.17 USD/bbl. This would mean that in comparison, the highest point reached was 78% higher than the 10y average, and 96% higher than the 5y average. This point is even more prominent if we look at the YTD change, as oil prices grew by 54%.

Brent oil prices (2010 – Today, USD/bbl)

Source: Bloomberg, InterCapital Research

With the approval of the phased embargo of Russian oil imports by the EU, the prices are only expected to continue growing, as there are several major factors outside of the ban itself that influence these movements. Let’s start with the most obvious one, that is, the supply of oil. As the supply of oil in the world is limited, not only by the amount of oil in circulation at all times, but also by the extraction rates and especially the refinement rates, the supply needs time to pick up, especially when the so-called „black swan“ events (events that are beyond of what is usually expected and can have severe consequences, like the COVID-19 pandemic, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine) happen.

Furthermore, even if both the extraction and refinement rates could be increased proportionately to the requirements, it still does not take into account the political will. This refers to the fact that the major oil producers, like the OPEC members (i.e. Middle Eastern countries like Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, and Qatar) are unwilling to massively increase their output to meet the increased demand, as this would flood the market and have a negative impact on the price, not to say that if the current situation resolves itself, their increased output will lead to losses. This stance is pretty evident if we look at the recent reports on the promised increase in production by the OPEC countries, an increase of 648k barrels/day for July and August, as compared to an earlier pledge of 432k barrels/day for the same period.

Other countries like Venezuela and Iran and currently in talks with the US and the EU to increase their exports of oil, which could together supplement more than 1 million barrels per day of additional production. Furthermore, the rest of the missing supply from lower Russian exports could be supplemented by inventory releases and an increase in U.S. shale production. The green transition that has been at the forefront of the EU’s economic transition should also be taken into account, especially because this is a long-term goal, oil companies (and by extension, countries) have yet another reason to refuse requests for significant increases in their oil production.

Meanwhile, the relaxation of COVID-19 measures across the world has increased transportation, especially car and air travel, which is also putting more pressure on the demand side. Finally, China, one of the largest economies in the world, is also slowly turning its strict pandemic measures around, meaning that if they do fully re-open, the demand for oil will be even higher. However, with Russia offering Asian countries discounts on their oil exports ever since the beginning of the invasion, hopefully, this should not have a severe effect on the oil prices.

On the other hand, several things should be taken into account before we give too negative of an outlook. Firstly, the ban is gradual, meaning that most of the member states will reduce their dependence by the end of the year, with several exceptions (mainly Hungary and Slovakia). There is potential that the US and the EU will reach breakthroughs in agreements with the OPEC countries, further boosting the amount of available oil. Lastly, the sheer political will needed to do an embargo on such an important resource as oil should also be taken into account.

If we were to compare it to gas, which the EU also imports a lot of from Russia, there is a significantly higher resistance to banning it compared to oil. In fact, at the moment, there are currently no clear plans for doing such a thing. What can be taken from this is the fact that if there weren’t alternatives already found for oil (like is the case for gas, at least at the moment) then the agreement on the ban wouldn’t have been reached, especially if we take into account that several EU countries get the vast majority of their oil from Russia.

As we can see, the situation is really complicated, with a lot of variables and uncertainties at work. Nevertheless, having all of this info at hand, we can ask the question: How will this affect the end users?

There are several possible answers. Firstly, as we have seen in the past few weeks, the prices of fuel (petrol, diesel), have been increasing proportionately with the developments in oil prices. This is, unfortunately, to be expected, and as the current geopolitical situation breathes a lot of uncertainty, with a potential for high volatility in oil prices. To somewhat counter this, and dampen the impact on end users, EU countries have introduced a plethora of measures, from introducing caps on fuel prices, to reducing excise duties and taxes.

With the approval of the embargo, how will this influence prices moving forward? Unfortunately, this is also a really tough question to answer, as it depends on a lot of variables. If the EU can find the alternatives for the Russian imports fast enough, and if the current situation in Ukraine does not escalate and/or lead to further sanctions, it is possible that the prices will remain at similar levels or even decrease. However, if the situation escalates, combined with a lack of complete alternatives, combined with let’s say China also deciding to re-open and buy the discounted Russian oil, then the situation will surely get worse for the supply of oil in the EU, and subsequently, fuel prices. What remains for the EU countries in any of these situations is to continue monitoring the prices and keep them at somewhat stable levels, by introducing new subsidies, or by further reducing taxes/excise duties. Caps on prices could also be further extended, but this one is the trickiest as it affects the companies the most, reducing the available cash to them at a time when prices are increasing, thus reducing available cash for maintenance and further investments into oil production, refinement, and distribution, which in the end, could also lead to an increase in prices.

With all of this taken into consideration, a new question arises: How far can the EU countries regulate prices, by influencing any of these factors? To better answer this, we took a look at how much the prices of Euro Super 95 have changed since the beginning of the year, as well as how different the pricing is with and without taxes, in different countries.

Comparison of Euro Super 95 pricing (EUR/l) across countries

Starting off with a comparison of Euro Super 95 pricing, we can see that in the region, Croatia has the largest prices, at EUR 1.87/l. Compared to Slovenia and Romania, this represents 20% and 11% higher pricing, respectively. This difference is even more profound when compared to Hungary, compared to whom the pricing in Croatia is 48% higher. However, compared to the Euro average, the pricing is about 4% lower. Even when compared to the countries outside the EU (Serbia, B&H), prices are 18% and 14% higher, respectively. If all the countries in the area are affected by the same global oil prices, then the only reasons for these higher costs can be excise duties and taxes, and of course, the margins for the distributors. But how much do these margins contribute to the price?

Croatian Euro Super 95 pricing (EUR/l), with and without taxes (2020 – Today)

Looking at the price of Euro Super 95 without taxes, it amounts to EUR 1.03/l. First comparing it to other countries, Croatia’s Euro Super 95 price w/h taxes is 21.5% higher than Slovenian price of Euro-super w/h taxes, 3.4% higher than Romanian, and 40.7% more than the Hungarian price. Compared to the EU average, however, Croatia’s price of Euro super 95 w/h taxes is app. 8.9% lower. However, this difference is even more staggering if we compare the price with and without these taxes. The Euro-super 95 price with the taxes in Croatia, is 80.5% higher than price w/h taxes, while in Slovenia it’s 83.3% higher, in Romania it’s 64.6% higher, in Hungary it’s 68.9% higher, and finally, in the Euro area average, the price of Euro Super 95 with tax is 82.7% higher than w/h tax. This means that in total, the Euro super 95 is more expensive both with and without taxes when compared to the region, but slightly lower when compared to the Euro area.

Taking this into consideration, how much do taxes, and how much do margins contribute to the overall price?

Taxes as a percentage of the total end consumer price, Euro Super 95, EU (%)

As can be seen from the graph, Croatia is not that far off compared to its peers to this extent, at 45% tax in the total pricing. Slovenia is the same as Croatia, Romania is at 39%, Hungary is at 41%, and the EU average is at 44%. Taking Croatia as an example, this would mean that out of the EUR 1.87/l paid, EUR 0.84 goes to the government. Last week’s announcement on reduction of excise duties and a cut to distributor margins (from app. EUR 0.11/l to EUR 0.086/l), means that the price is currently managed somewhat. The government still has some leeway to reduce the overall taxes and excise duties, something that they have been doing, decreasing the percentage of taxes from app. 54% to 45%, as can be seen in the graph below:

Percentage of taxes in total end consumer price in Croatia, Euro Super 95, (2020 – today)

One thing that should be noted from the graph is that part of these taxes is fixed, meaning that no matter what the price of oil is, those costs remain the same, which would mean when the price was lower (as was the case last year and in 2020), the percentage of taxes would be “higher”. These are the types of taxes (excise duties) that the government reduced, the fixed part, while the VAT which is based on the percentage of the total price still remains.

Looking at the higher petrol retail prices w/h taxes in Croatia, one can conclude that in Croatia retailers pay higher prices for Euro Super 95 from refineries and considering they import most of the fuel, it means that it’s both more expensive to import it, and the government takes higher taxes on it. If the prices of oil continue increasing, as taxes (VAT) are based on a percentage of the price, so will the overall price.

So what can we learn from all of this data? Firstly, the whole situation is extremely complex and has a lot of factors at play. Secondly, it’s almost impossible to predict how the situation will develop. And finally, the government still has room left to influence prices, but to what extent it is hard to predict, as further reduction of taxes on fuel also influences their ability to manage their budget, something that in the longer term could also have negative consequences.